Claire Cooke transitions from being a Division I athlete

*BEEP* BEEP* BEEP* The alarm sounds. She rolls over in bed and quickly hits snooze. It’s 5:30 a.m.

*BEEP * BEEP * BEEP* The second alarm sounds. Her eyes bolt open, and she fumbles with the phone to hit snooze again. It’s 5:38 a.m.

*BEEP * BEEP* BEEP* The third alarm sounds. She hits snooze one more time. It’s 5:40 a.m.

*BEPP * BEEP* BEEP* The snooze goes off repeatedly. She presses stop on her phone. It’s 5:45 a.m.

Time to start her day. She is at work by 5:50 a.m.

Claire Cooke starts her shift before the sun is even beginning to rise. She greets and check-ins the early risers who come to the fitness center at Syracuse University’s Barnes Center at The Arch. It’s 9 a.m.

Once her shift is over, she works out. It’s 10 a.m.

She quickly hops in the shower, packs her lunch, and drives to the Gebbie Speech, Language, & Hearing Clinic on South Campus. It’s 10:45 a.m.

She goes from class to clinical and back to class in the same windowless building. After learning, working with patients, and learning more, she is ready to see the sun again… except the sun is gone. When she finally walks out the doors, the sun is set. It’s 7:30 p.m.

She connects with her faith on Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday nights and attends church groups. Finally, she returns to her apartment to eat dinner and start her homework. It’s 9:30 p.m.

Claire Cooke is no stranger to early mornings and late nights. Her life has always been like this for the last five years. She keeps her calendar filled, running from one thing to the next. But this year, it has been filled with different events.

Before this year, her schedule consisted of 6 a.m. lifts, 9 a.m. classes, 2 p.m. film sessions, 3 p.m. practices, 6 p.m. classes, and 9 p.m. dinners. Cooke never thought about having time to work and go to church.

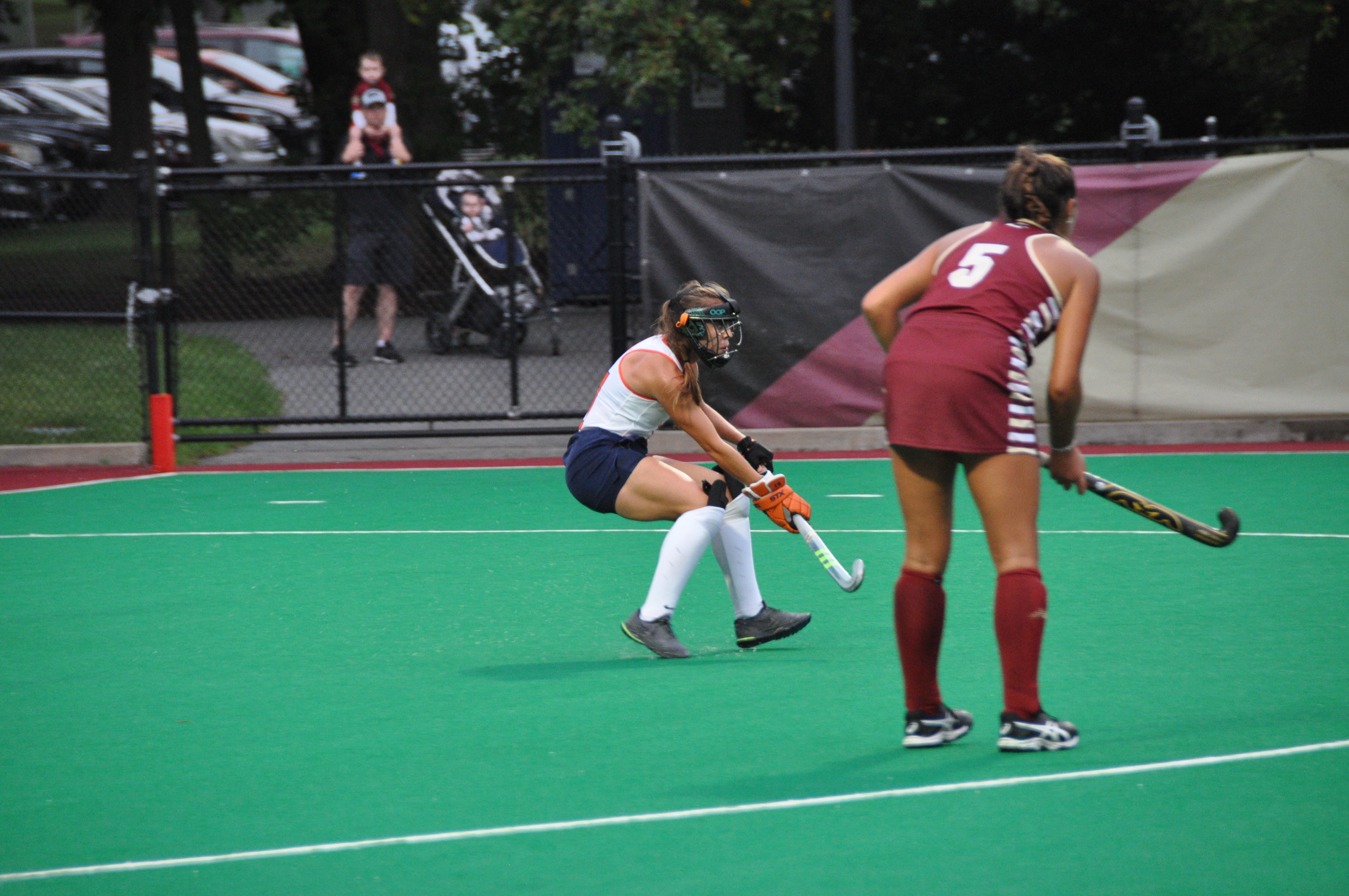

The moment Cooke’s life changed was November 14, 2021, at 2:36 p.m., all at the sound of the buzzer. Immediately, her eyes swelled with tears as she watched the Maryland field hockey team storm the field in celebration after winning the second round of the NCAA tournament. The final score was 2-1, ending Syracuse’s season.

From that moment on, Cooke began transitioning from being a collegiate athlete. The transition is comparable to the grieving process: there are multiple stages until acceptance, and it’s a journey of mixed emotions.

First stage: Loss. After the game, as players went to the locker rooms and the hundreds of fans left to begin postgame celebrations, Cooke stood side by side with her two other teammates. They stood not together for warmth but for comfort. The fallen leaves from the trees surrounding the turf created a desert environment on the empty field. Her eyes were watery as she looked down at the Syracuse jersey, knowing she would never wear it again. She was overwhelmed with sadness, knowing she was saying goodbye to her teammates, coaches, and field hockey.

But no matter win or lose, eventually, there will be the last game for every athlete. It will be the last time they lace up the cleats and put on their jersey. For college students, most of the time, it comes at the end of their four years of eligibility. According to NCAA statistics, less than 2.5% of college athletes are drafted to their respective sport’s professional league.

For Cooke, her end came after five years on the Syracuse field hockey team. In her freshman year, she redshirted, allowing her to maintain her four years of eligibility by sitting out for the season. She had torn her ACL at the end of September, her senior year of high school. By the time she was cleared after surgery, she was not ready to play at a top three school in the country. After her freshman season, she knew she wanted to stay a fifth year to play her full eligibility. At the end of her four years, she completed a Bachelor of Science. Then she began a two-year Master’s program focusing on Speech-Language Pathology to stay for a fifth year.

Second stage: Sweet. Cooke finished her playing career at the end of the fall semester, with one month left of school. She had a sense of freedom and no longer had to carry the extra stress a captain holds. She celebrated with her friends and didn’t have to worry about lifting the next day.

Third stage: Bitter. But the reality of no longer being a part of the team did not hit until the spring semester.

“The first month after it was fun. I would say it probably didn’t settle in as like a sad or bad thing until maybe like February or March,” Cooke said.

Cooke was transitioning from 20 hours of practice, plus games, plus travel time, plus time with your team, plus academics to only having classes. It was free time that she hadn’t had in years, and a part of her was left on the field.

It was the first time Cooke was not on a team since she was five. Her passion for field hockey started once she picked up a stick in ninth grade. At the time, Cooke wanted to play lacrosse in college, and being highly motivated, she wanted a way to stay in shape. But playing soccer and club lacrosse in the fall wasn’t enough for her, so she picked up a field hockey stick to add to the list of activities. That’s when she fell in love. She dropped everything else. It was just her and her stick. She would spend hours in her backyard by herself practicing. She would wake up at 5 a.m. to practice by herself. She knew nothing but found it fun. She would bring her hockey stick with her everywhere.

But without the sport and without the team, Cooke struggled. Field hockey is what she loves and was what she did for fun. Even going for a casual jog was a challenge after being in a performance environment for so long and not having to hit a specific pace. She deleted all her running apps.

Fourth stage: Transitioning and redefining yourself. The hardest part for Cooke was being on campus this fall but not competing. She had to let that part of her go and try to find a new normal.

Cooke is in the second year of her Master of Science degree. She still has another year of eligibility because the NCAA granted athletes an extra year due to Covid. But she had to make the difficult decision to not play this season.

Logistically it wouldn’t have been possible for her to compete due to the demands of her degree. She wouldn’t have been able to attend every practice because her classes were late into the night. She wouldn’t have time to travel to games if she wanted to complete her degree.

“I was at a point in my life where I had to choose school or hockey, and I had chosen school. But the year before, I had intentionally chosen hockey. I had set the whole thing up to kind of like get me in that situation.”

Her roommate, Kailey Smith, understood the struggle Cooke was going through. Smith played on the team with Cooke for four years. They have been roommates since their freshman year. Smith decided not to play a fifth year like Cooke, even though she had another year of eligibility. She sat on the sidelines as she watched her roommate play on what was no longer her team. Smith had experienced the same emotions that Cooke had just a year prior.

“It’s hard. I know when I first went to a game after I was done, I cried walking back into Coyne [the field hockey stadium] just because you’ve been a part of this thing for so long and it means so much, and then all of a sudden, it’s over… I think it really is a personal journey that everyone has to go through, just sort of like re-find yourself. You know, you spend four years here, or five years, however long, but then even before that in high school, like getting to this point really is your life for—I don’t know, field hockey was my life for eight years. All of a sudden, it’s just done. So, in that way, it sort of consumes who you are,” Smith said.

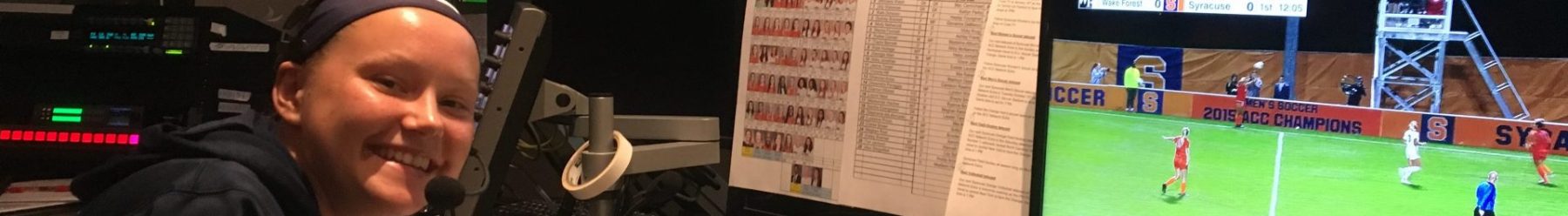

Fifth stage: Acceptance. Cooke has been finding ways to navigate her new lifestyle. She would occasionally watch practices when her classes didn’t conflict. For home games, she would be an announcer on TV for ACC Network. But being around the team and seeing her former teammates didn’t make her miss the game any less.

“It’s been weird to be here and not play. I think that’s just the most odd piece of it, that you’re still in the same space, same like everything, but you’re not doing it… Losing all of your community is hard. You go from 35 of your best friends to not having that. You don’t have that support in everything you do because you’re not doing it together.”

Cooke was able to find support in her faith. She could go to church on Sundays, a day she wasn’t free because of practice. She also found going to small groups to be very instrumental in her being able to cope. She attended bible study groups through the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and the Salt Company.

“In the spring, it felt like I was free verse this past fall, it felt like I was missing something. It was weird broadcasting the games. It gave me the community to talk about the small things I’m struggling with. Someone to walk through life and who knows really big things about you, from your struggles in your relationships to working out. That was something I was missing this fall… It [the spiritual aspect] helped me get back on my feet.”

Her legacy. While Claire Cooke was never the star player on the field, she has left a lasting impact off the field.

Andrea Bradley, Syracuse’s head coach, praised Cooke’s leadership and intangible qualities. Even though Cooke wasn’t on the team, she still served as a mentor to players.

“That was great having her to be able to come to practice every once in a while and offer perspective to some of the younger kids on the team or be there as a resource in how to like manage leadership situations,” Coach Bradley said.

Even on the sidelines, Cooke brought excitement to the field when she came to practices.

“Obviously, the freshman don’t know her the way that the sophomores, juniors, and seniors do. But as soon as she stepped on the field, it was like everyone was happy to see her… We really showed the freshman that she is so important to this program in everything that she ever brought to the field and also off. So we really explained to them that she’s a very important alumn,” junior Eefke van den Nieuwenhof said.

Once a week, the two would meet for coffee. Van den Nieuwenhof learned about leadership from her this season as she took over Cooke’s captain role. She would ask Cooke for advice and ask how to handle situations. Van den Nieuwenhof had to figure out how to motivate the team as Cooke did.

“She is so important to us because of what she has done in her time that she was here and also her whole appearance on the field. She just makes everyone go like a thousand percent every single day,” van den Nieuwenhof said.

People around her wanted to do better. She pushed herself and everyone around her.

While her name may not be recognized in the record books, her name will always be remembered in the Syracuse field hockey program.